It’s a summer morning in downtown Boston when a tall man in linen, spectacles on a cord around his neck, saunters into the Godfrey Hotel coffee shop like he’s arrived at a South American art party. He begins talking to people magnanimously, like he owns the place—and he does. His name is George Howell. His name is also on the window, and his legacy in Boston, and all of coffee, precedes him.

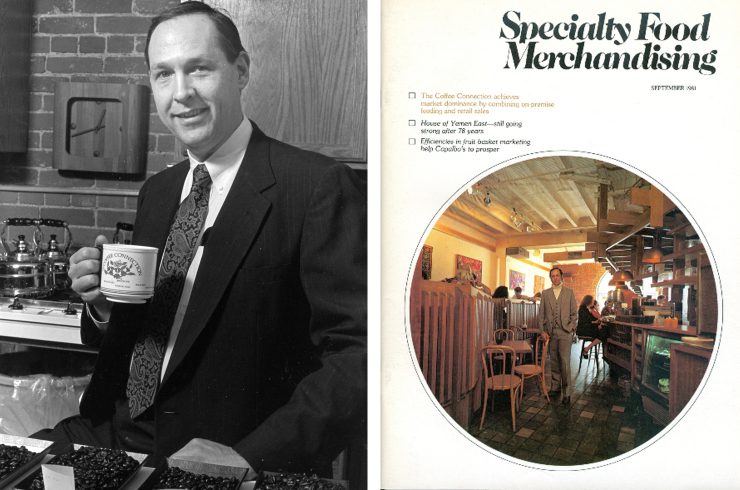

Howell’s been an integral part of shaping specialty coffee’s trajectory since the 1980s through his chain of Coffee Connection cafes and early enthusiasm for international coffee competitions like Cup of Excellence, quality initiatives at the farm level, and advocacy for a lighter roast—and he’s well-known not to bite his tongue on a strong opinion. Arguably an international influencer even over those who may not always agree with him, Howell is also notably credited as inventor of the Frappuccino, a distinction that somehow does nothing to undermine the gravitas of his reputation.

In 2016, after a long absence from Boston’s retail-cafe landscape and at the age of 71, Howell is again able to claim two of the city’s top quality cafes: a high-volume kiosk in the Boston Public Market, and his most recent opening, a sleekly designed space within the Godfrey outfitted perfectly to share his lifelong coffee message as well as his other lifelong passion for showcasing the indigenous Huichol art of Mexico.

Sprudge sat down for—let’s be honest—a very, very long talk—with Howell to find out more about his journey thus far.

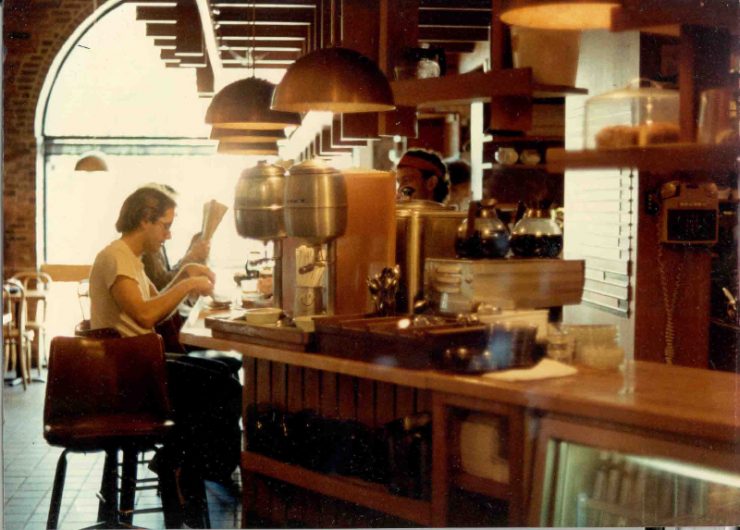

At the first Coffee Connection shop.

Sprudge: Where’d you grow up and what were your foundational coffee experiences?

George Howell: I grew up in Hasbrouck Heights, and later Ridgewood, New Jersey, till the age of 13, and then my parents hauled me off to Mexico. I drove with my father in a Plymouth station wagon in 1958 from Jersey to Atlanta through the segregated South, and I was shocked. I spent the first six months in Acapulco, and then we went to Mexico City. My mother threw me into a lycee Franco-Mexican which was all in French. I went through the whole high school system in French school, which was French government-run, and that threw me into the whole cafe culture. That was my first real sense of the cafe, was the cultural piece. I do remember earlier in New Jersey my parents making coffee in a siphon, which then got replaced with a percolator of course.

You were born with a condition that affected your mobility, and had knee surgery in Mexico as a teenager. How did working around that shape your path in life?

My knees and the French school both directed me to more intellectual and aesthetic pursuits. A whole year in solitude pretty much with one knee surgery and then the other, and private lessons. I became a superfan of classical music and jazz. I don’t like big orchestra jazz, it’s more the quartets and so on, so what I really followed was Coltrane—I was lucky to have actually seen him play—Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, and more recently, William Parker.

And from music you drifted into the visual arts?

I wasn’t able to get to Yale till I was 19, and there I studied history of art, but also contemporary French and Spanish literature. I left in ’67, in my third year. The whole music scene, the whole art scene, really caught up with me. I spent my weekends in New York. The other thing was avant-garde painting, so in the daytime I’d go to New York with a close friend and we’d go to the galleries and museums in the daytime. I left [school], thinking I’d come back to resume my studies when I was a little more focused. I dabbled in art, went to the West Coast, and there, met my closest friend, Juan Negrín.

Juan would go to Mexico in the early ’70s and bring back art from there…Juan connected to those who were doing original [yarn painting] art that was being copied, that had mythological meaning. I would exhibit, first in Berkeley, then in LA. I had a small trust fund that I was able to live off of and it enabled me to do these things. The 1960s was the age of rebellion—NO ONE was going to tell me what to do, no matter what. And interestingly enough they couldn’t, because the trust had been set up by my grandparents.

Beans for sale at The Coffee Connection.

And—to try to follow the thread—your connections to underground music and art turned you into a gallerist…which eventually turned you into a cafe owner?

The first coffee connection in Harvard Square was my first place to exhibit art.

I met my wife [Laurie Howell] just before I moved out of New Haven to California. In ’73 I decided the whole scene on the West Coast was dying; at that point there is an anger and a bitterness, a defiance, that arrives. We had two kids already and number three on the way, and I did have to make a living.

It’s a well-worn story how I drove with the two kids in the car with my French press and grinder going to the men’s room and grinding coffee and brewing coffee at the Howard Johnson’s counter. I’d become used to drinking coffee on the West Coast and I was drinking French presses all the time, and I’d always have three or four people sitting down at the restaurant asking “What are you doing?” And here I was explaining coffee before I was even in the business. So I came back [east], and the coffee was dreadful. We’d seen the success of Peet’s and other places—I was never drinking coffee from Peet’s, it was too dark, but there was a place called Capricorn that was connected to Erna Knutsen.

So you decided to open The Coffee Connection when you got back east?

We came up with the idea in ’74 and opened in April of ’75. My wife came up with the name, because of course that was the time of the French Connection. The minute she said it, we all knew that was the name.

It was a space [in Harvard Square] that was originally a garage for horse and buggy. At first it was 600 square feet, but within a year it was passed over to new owners, and we were told that we had to triple our space or get out, and that’s when we got our first Small Business Administration loan, which saved our necks. So we built the Coffee Connection [people are] familiar with, and were [also] able to make a major yarn painting statement.

At The Coffee Connection you roasted your own coffee, at a time when the pedigrees of coffee weren’t prioritized. How did you elevate the importance of this to your customers—and in turn, to coffee drinkers nationwide?

I couldn’t put a roaster in Harvard Square because [the shop] was three floors of concrete, so I had to PROVE that we roasted it, and that’s where the roast date was invented. All the coffee was in open barrels so the customer could see, and they could see the roast date on every one. No other place had roast dates. So we created a much more educated base. The first years, I’d go and roast in Burlington a good half-hour to forty-five minutes away, and then bring the coffee in and do retail and be wiped out. I never really got into doing the whole barista thing, which was not even real in those days, but I couldn’t make a good cappuccino to save my life.

How did you source your coffees at that stage?

When we first started to do the business, a salesperson actually visited us and brought three bags of coffee: a Colombian, a Brazilian, and a Costa Rican, and he showed us that “you can blend these this way and get a Kenyan,” or “blend them this way and get a Jamaican”—complete hocus-pocus. That’s what [got me] determined to buy a roaster, and that’s what connected me to Erna Knutsen, who was the ONE PERSON revolution personified. Truly.

Literally all the coffee we got for the next 10 years or more, 95 percent was all from her. That meant buying it out of San Francisco and trucking it all the way here, and there were people I could buy from on the East Coast, but they did not compare. Even when other importers started on the West Coast they could not hold a candle to her, she really dominated. It wasn’t until the late ’80s till there started to be some actual competition. I was perfectly happy to buy from someone else if they were better. I did the research, but there wasn’t.

What kinds of coffees were you getting into? How did you showcase them?

Most of the coffees back then for me were blends, and then you’d also have Guatemala Antigua and Kenya AA. It was assumed that that was what you could get. It wasn’t until Erna introduced the Dorman’s coffee, in 1988-89 as I recall, that it dawned on me that you could buy from individual co-ops and farms.

I came on the idea of doing French press for every single coffee we offered, so from Day 1 when we opened in April of ’75, any coffee we had at retail you could order made on the spot for you as a French press. Espresso? What was that? Literally we had a home espresso machine, it was a Swiss machine, we could make about four espressos, run out of water, have to say to people, “There’s no espresso for the next hour while we cool the machine.” Years later when we tripled the space we had to add an espresso machine, a six-group Bezzera, all copper-sheathed with a handle that you pull down. That was in 1976. It caught people’s attention, I’ll tell you that.

The Coffee Connection, New Canaan, Conn.

How big did The Coffee Connection eventually expand to be before you sold the company to Starbucks?

We got up to 23 stores—it varies, because my memory is faulty. It was opportunistic growth, because I’m never satisfied with what we are. I’ve always believed that if you stay still you will be covered over. You actually go backwards.

I was a little bit aware of Starbucks before Howard Schultz took over, but when Schultz took over you had to have your head in the ground not to have heard about them. So in ’88 I went to Seattle, because this guy wasn’t talking about regional. He was talking about covering the country and dominating, and I needed to see what that potential nemesis was all about.

Starbucks had a few cafes already in downtown Seattle under Schultz. I saw how the espresso machine was turned around, and the customer service piece, the functionality of it—and that was something I retained immediately, I was really impressed how that worked, so I came back east with the intentions that new Coffee Connections would incorporate the good things that I saw about Starbucks.

I certainly respected Schultz, and I knocked on his door actually, I met him and I asked him point blank, “Are you coming to Boston?” and he said, “No, but perhaps down the road, you and I can make history together.”

Whoa. Anything else happen in Seattle?

A company called Torrefazione—later purchased by Starbucks—was serving iced cappuccino in a granita machine. This concept had been written about for many years by Ted Lingle, then the executive director of the SCAA. I tasted it and knew it was something I needed to do. A friend gave me the formula, which is coffee, sugar, and water, really strong in a granita machine, and I handed this over to my marketing associate, Andrew Frank, who came up with the name Frappuccino [from the New England “frappe”] and got the ratio of sugar to coffee-milk exactly right so that the mix would not crystallize.

So the Frappuccino it was, and we tried it in Harvard Square, and people loved it.

Ethiopia 2012

Since that time, sourcing has become as much your identity as anything else. Tell us a bit about your leap into that world.

It was in ’88 that the big change really takes place, and that’s with the beginning with La Minita. Bill McAlpin and Carol Kurtz, who is now his wife, come to the East Coast and are traveling, driving up the coast, knocking on doors and saying, “We have coffee here that we brought to Virginia, and it’s for sale green, and it’s better-quality Costa Rica than anything you’ve had, why don’t you taste it.” So we cupped it—we hardly knew what cupping was—comparing it with what we had, the best Costa Rican at the time, that we were buying for $1.85 [per pound]. I still remember that—and his was $3.50.

We started to sell it, we promoted it, and it became one of our bestsellers over several years as people really started flocking to it. To this day we still have followers of La Minita.

At the same time, Erna invited me to go to Kenya and meet Jeremy Block. Jeremy had bought, just a few years earlier, the company Dorman’s. He had become an official cupper there and he was bringing standards up that were phenomenal, and very much concerned at the time with improving quality in Kenya and giving incentives to farmers.

I didn’t sell [The Coffee Connection] until ’94, so somewhere around ’89 I started buying from him, and we’re going on 11 stores by that time, and by ’93 i’m buying 12 lots of Kenya coffees [annually], and those lots are anywhere from 40-to-120 bags each, so, no small quantity.

I was cupping [those] coffees and samples and then picking the 12 out of the 50 or 100 or whatever number of samples. After a year or two doing this, Jeremy suggests doing a competition, and it would be The Coffee Connection competition. He comes up with the idea that it’s like the Stanley Cup, a trophy that you get to hold for one year.

So we along with the Dormans staff selected the coffee out of the top 12 we purchased. It was $10,000 that we would contribute—maybe $5,000—to the first-prize winner, to a co-op. I think it was one third in cash to the actual people at the wet mill who managed it, because they were the make-or-break doorway to quality, because the farmer produced the cherry, but it was there at the mill that the fate of that coffee was decided. The other part, the two thirds, went to improving their infrastructure. That’s how we set it up, and then I went to Kenya and gave speeches at the mills.

Cup of Excellence Brazil, 2001

So by this point you and other international buyers were beginning to travel regularly to coffee farms?

This whole thing about traveling to farms is an innovation that’s brought in, really, with Cup of Excellence. Whether it would have happened at the same speed and at the same time with or without CoE, I leave for other people to decide.

And just as you developed a passion for traveling to origin, Howard Schultz did finally come knocking?

[Starbucks] had approached me two other times to buy The Coffee Connection. They were starting to have their eyes on coming to Boston, and we already had 12 to 15 stores in the area. By the third time we had gotten venture capital, and we had doubled the size and expanded outside of Massachusetts—one store in Connecticut, two in New Jersey and one on Long Island. We were looking in Manhattan, we were gung-ho.’94 comes along, I’ve got six kids, a bunch of them are getting ready to go to college…but I didn’t want to see it go, I wanted a legacy. So we came to an agreement that [Starbucks] would keep two thirds of the stores as Coffee Connection for the first two years to try it out, and that I would also have the right to buy all the Costa Rica and all the Kenyan coffees for Coffee Connection and they would do the rest. They hired me as a consultant, so there I was, being paid for the next two years, the main function I had was to help them do a lighter roast, which they never succeeded in getting. They did a lighter roast than the Starbucks roast, but not the blond that they finally came up with more recently. And that really was, later on, great for me in terms of credibility and value. That was a critical turn at that time.

Dark roast was [like] coming into a very dark room, seeing soft glows from multiple light sources, whereas light roast was walking out of that dark room into the sunlight and being blasted by the acidity of the sun. I think it’s a good analogy to this day.

George Howell and Geoff Watts at the 2002 Nicaragua Cup of Excellence.

Once your consulting gigs and non-compete with Starbucks were over, you then began selling coffee under the Terroir label?

In 2003 we set up a roasting operation in Acton, Mass., which we still have, and we open Copa Cafe, and this is where I get in over my head. It became a small-plate restaurant, a 4,000-square-foot place with a super cafe inside. The cost of operating that thing was way over—we lasted for about a year, and decided to shut it down. We were left with the roasting operation and no cafe, so the move was toward wholesale as an immediate solution.

So we had mailorder and wholesale. But overall wholesale is not where I’m dealing directly with the consumer, and that is frustrating to me. Restaurants have other big issues to solve for themselves…and also the culture in restaurants, especially on the East Coast, is that coffee is an afterthought that comes after you’ve presented everything you can throw at them in terms of quality. So all of that contributes to frustration on my part on the one hand, I’m not doing what I really want to do, and I’m not getting the word out that I really want to get out, and I’m not buying as much from the farms as I really want to get.

There is a cafe market more and more on the West Coast, but coming to the East Coast. Some cafes then become roasters, and it’s critical that we get back into direct relations with consumers where we are able to educate people.

So we opened up the Taste Coffeehouse about 4 or 5 years ago, I’ve lost memory exactly when, in Newtonville in the [Boston] suburbs. We bought basically a converted diner that was being run by a person, Nik Krankl. We reduced the food dramatically after a year, cut crepes out. Once we started to really get that cafe in order and understood the new world of retail coffee is where we really started a serious search as to where we would locate a key cafe, one that would be the showcase immediately.

And that’s where we’re sitting now, in the renovated Godfrey Hotel?

Yes. It’s in an area that’s been completely redeveloped, in the downtown cultural center of Boston, with two universities right here with 14,000 students, where you have everything from poor to super-rich combined, and lots of travelers. This is the kind of hub with spokes that we were looking for.

So now that you’re back on the Boston cafe map, what’s changed since The Coffee Connection days?

There’s real competition as opposed to nonexistent competition. With TCC there wasn’t just no competition here, there wasn’t competition on the whole East Coast as far as I’m concerned. Boston still only has a handful of what I consider Third Wave cafes, which to me is very simple, light-roasted, terroir-based coffee. I think we’ve seen a gathering sophistication in terms of people in the business. There are baristas going around now who really do know something about coffee and who are fun to talk to, and we have latte showdowns and so on that we participate in. And that’s all new, for this place.

The spread of coffee has grown dramatically, not just in terms of single farms but also in terms of price. You can get a really good wine for $10, you just have to look. And if the coffee industry can develop in that way, you’re going to have that too, so you’re going to have entry-level coffees that are really good that should be paid more for, and [they’ll] bring people in and average quality will rise. The role we want to play is always bringing it to that central point. If we lose the farmer as central, we will ultimately lose the quality as well.

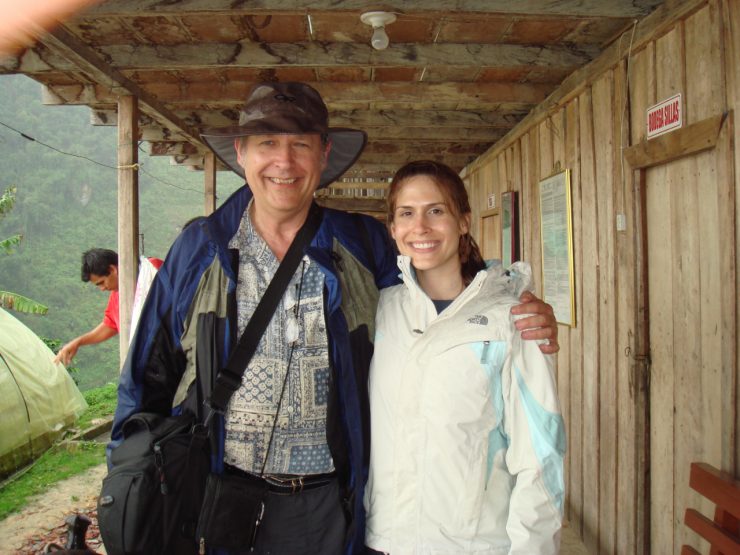

George and Jenny Howell in Colombia, 2008.

As you’ve grown through the years, you’ve had the pleasure of making George Howell Coffee into a real family business. What’s your daughter Jenny’s involvement? How closely do you get to work together?

Jenny was an oddball in the sense that when she learned to stand up, actually went for the black coffee, and we had to take it away from her. She’s got really great ability to taste, the one time she competed for the cupping championship she took second, fairly easily I think. The year before this she went to Kenya and really cupped a lot, and walked away with what turned out to be the first-place winner in the gourmet competition. We bought what we could.

How closely involved in the green buying process are you these days?

I never cup alone, ever. I always cup at least with Jennifer, and sometimes with Sal [Persico, barista and trainer]. There are a few things where I’ll say, “I want it,” but very rare. Usually it’s a consensus thing, and we end up agreeing.

I’m going to the key origins once a year at this point, I’ve found that I’ve had to spend a lot of time here because of developing the cafe. We’re still a very small operation, and a complex one, with the wholesale and the mailorder and so on. It’s also developing the quality here and working here toward expressing it. So, that’s where Jennifer comes in too. I’d like to visit Peru this year; I’d like to resume Ethiopia, now that the cafe is up and such.

Travel is very important in order to maintain those relationships, we’re sort of cross-pollinators; we’re learners in order to cross-pollinate, and I mean that in the widest term possible—it’s from consumer to ourselves to other farmers in other parts of the world. You can bring a Kenya concept to Guatemala, or vice versa, as we’ve seen happen.

With Walter Mathagu in Kenya, 2016.

What opportunities has opening these new cafes afforded you in terms of bringing some of your coffee philosophies—of which I know you have many—to a greater audience?

This cafe has a daily education center for staff and for customers. We want to draw people in and have them be curious. Anyone that’s curious is going to love it here. I’ve dreamed of this—if someone went to the Harvard Square Coffee Connection, we had retail completely separate from our bar, which allows you to really center and spend time with the consumer. It also allows us to do showdowns here, and that sort of thing. And to experiment with equipment, and also a The Doctor is In location. If you’ve bought our coffee and you can’t make it as good as what we serve here, bring your coffee equipment and grinder here and we’ll actually brew it the way you do and we’ll see.

And finally: you’ve never been afraid to speak your mind about your coffee opinions, even if they rankle the feathers of others you may respect. Has there ever been a time you’ve regretted saying something?

I’d like to think I haven’t but I know I have, because you can’t say what I say and not. I’m sure there are dark roasters who don’t exactly like me. Cold brew—I’ve been very clear about my thoughts about that. I’ve moderated that to some degree…realizing the floodgates are open, this is a reality, and there are going to be people who love it. It’s a valid drink in and of itself, just don’t tell me that it’s terroir-based, and take it for what it is.

[Howell pauses, trying to think of another instance of outspokenness.]

Maybe I have a better memory for the good times.

Come back next week for our glimpse into the game-changing George Howell Cafe at the Godfrey Hotel.

Archival photos courtesy George Howell.

Liz Clayton is the associate editor at Sprudge.com, and a staff writer based in New York City. She is the co-author of Where To Drink Coffee, to be released on Phaidon in June 2017. Read more Liz Clayton on Sprudge.

The post George Howell: The Sprudge Interview appeared first on Sprudge.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8200593 http://sprudge.com/george-howells-entire-fucking-life-story-111865.html

No comments:

Post a Comment